On Tuesday, January 20, 2009, the presidential oath of office was administered for the seventieth time, the fifty-eighth such ceremony in a location in Washington, D.C, the fifty-second at the United States Capitol, and the seventh on the west front of the Capitol; but even more historically, for the first time in American history it was taken by an African American.

The 20th Amendment to the Constitution provides that the term of the President begins at noon on January 20; however, before executing the powers of the office the President must take the following oath as specified in Article II, section 1 of the Constitution:

"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

1789: George Washington’s First Inauguration

Prior to 1937, inauguration day was set on March 4th (first by act of Continental Congress, September 13, 1788, and then by act of Congress, March 1, 1792; except when March 4th fell on a Sunday, public ceremony Monday). The first inauguration, however, didn’t take place on March 4, 1789, but nearly two months later on April 30th.

Because Congress met in Federal Hall in New York City, Washington went there to take the oath of office on April 30th. He went to the Senate Chamber on the second floor, where he was escorted out to the balcony to take the oath. Because no Supreme Court justices had yet been appointed, the oath was administered by Robert Livingston, Chancellor of the State of New York. The Bible used in the ceremony had been borrowed from nearby St. John’s Masonic Lodge when none could be found in Federal Hall. After Washington repeated the 35-word oath, Livingstone turned to the crowd and said, “Long live George Washington, President of the United States.” Livingston raised the Bible, Washington bent over and kissed it, and Livingston turned to the crowd and said, "Long live George Washington, President of the United States." The flag was raised, artillery fired, and all the church bells rung. The President then went back into the building and delivered his inaugural address in the Senate Chamber before both Houses of Congress.

Although it has become part of inauguration folklore that when President Washington recited the oath of office he concluded with the phrase “so help me God,” no contemporary account mentions Washington adding the phrase.

1801: Jefferson’s First Inaugural

The first inauguration to take place at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., was one of the most significant in our history. Thomas Jefferson’s March 4, 1801, inauguration was the first instance in which the presidency changed political parties. It was also the result of the first time an election had to be decided by the House of Representatives. Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in the electoral college vote, and the House did not break the tie in Jefferson’s favor until only two weeks before Inauguration Day. President John Adams left town, rather than go through another humiliation.

Only one wing of the Capitol, the old Senate wing, had been completed, and the swearing-in ceremony was scheduled for the Senate chamber.

Jefferson walked the short distance from his lodgings at Conrad and McMunn’s boardinghouse on New Jersey Avenue. Adams had left seven horses and two carriages at the White House stables, but Jefferson preferred to walk, escorted by several members of Congress and a crowd of onlookers. He had earlier written to Chief Justice John Marshall asking him to administer the oath and to see if the oath prescribed in the Constitution was the only one he had to take. Marshall, who also was acting Secretary of State under Adams, said he would be happy to administer the oath and that as far as he could determine the oath prescribed by the Constitution was the only one he needed to take.

The semicircular Senate Chamber was crowded with spectators as Jefferson gave his inaugural address, carefully worded to reassure his Federalist opponents that the federal government would continue. "We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists," he said. One of his listeners, Margaret Bayard Smith, wrote her sister about the event: "I have this morning witnessed one of the most interesting scenes a free people can ever witness. The changes of administration, which in every government and in every age have most generally been epochs of confusion, villainy or bloodshed, in this our happy country take place without any species of distraction or disorder."

Chief Justice Marshall administered the oath following Jefferson’s inaugural address. The new President, accompanied by Vice President Burr, Chief Justice Marshall, and others walked back to Jefferson’s boardinghouse, where he received citizens who called on him. At dinner, Jefferson insisted on sitting at his usual spot at the foot of the table, furthest from the warmth of the fireplace. Jefferson’s second inaugural was distinguished by the first inaugural parade, an impromptu, spontaneous procession that escorted Jefferson down Pennsylvania Avenue back to the White House.

Jackson’s Inauguration

In 1829 the inauguration of Andrew Jackson as the seventh President of the United States moved the ceremony to the East Portico of the Capitol.

Because of the crowd at the Capitol’s east front, Jackson entered the Capitol through the west front basement door. A ship’s cable had been stretched across the east front stairs to keep the crowd back. One eyewitness recorded:

Never can I forget the spectacle which presented itself on every side, nor the electrifying moment when the eager, expectant eyes of that vast and motley multitude caught sight of the tall and imposing form of their adored leader, as he came forth between the columns of the portico, the color of the whole mass changed, as if by miracle; all hats were off at once, and the dark tint which usually pervades a mixed map of men was turned, as by a magic wand, into the bright hue of ten thousand upturned and expectant human faces, radiant with sudden joy. The peal of shouting that arose rent the air, and seemed to shake the very ground. But when the Chief Justice took his place and commenced the brief ceremony of administering the oath of office, it quickly sank into comparative silence; and as the new President proceeded to read his inaugural address, the stillness gradually increased; but all efforts to hear him, beyond a brief space immediately around were utterly vain.”

At the close of the ceremony, the crowd pressed forward to greet Jackson, the cable broke, and the President had to retreat back into the Capitol and leave by the west door where he mounted a horse and rode back to the White House.

1857: Buchanan

James Buchanan’s March 4, 1857 inaugural ceremony was the first inaugural photographed—by John Wood, who had been hired by Montgomery C. Meigs in 1856 as photographic draftsman at the Capitol to document the construction. Of the photograph, Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter wrote:

“A crowd of 50,000 people impressed on paper as it was impressed on the retina of the eye from the stand point of the instrument. . . . By examining it with a glass you can see Mr. Buchanan distinctly . . . you will observe that nobody is giving much attention, which arises from the fact that nobody about where I was could hear one word of the address.”

Buchanan’s inauguration also was the first time that members of the congressional committee overseeing the inaugural ceremony escorted the President and President-elect from the White House to the Capitol. Note also the barricade to keep the crowd back.

1861, 1865: Lincoln’s Two Inaugurals

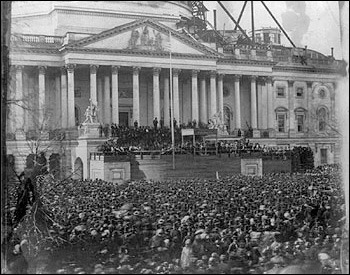

Lincoln’s First Inaugral, 1861

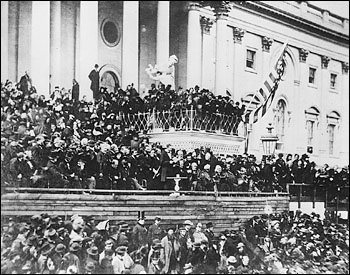

Lincoln’s Second Inaugral, 1865

Lincoln’s first inauguration took place in an atmosphere of danger and apprehension. Seven Southern states had seceded and Jefferson Davis had been inaugurated President of the Confederacy two weeks earlier. Troops guarded the inaugural route and the President even warned a friend that it would be best if women remained indoors on inaugural day. Nevertheless, Lincoln and departing President James Buchanan rode in an open carriage to the Capitol, flanked by a mounted guard.

The Capitol was still a work in progress. The two new wings designed by architect Thomas U. Walter and constructed by Army engineer Montgomery C. Meigs had been completed and occupied, but the cast-iron dome was still under construction. Its completion, Lincoln is reported to have said later, was a sign that the Union would survive the Civil War.

Lincoln’s second inaugural came just as the Civil War was drawing to a close. The weather was appropriately sullen. Days of rain and wind had left streets impassable with mud. A war-weary President ennobled the occasion with his inaugural address which many consider the greatest speech in American history. His second inaugural address is a somber, deeply-felt, and articulate meditation on the meaning of the Civil War to the soul of America. To those in the North who saw the war as a divinely-ordained crusade and who sought to exact retribution on the conquered enemy, he urged mercy tempered by understanding. Both sides, he reminded listeners, "read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully." The last paragraph is the most famous of any Presidential Inaugural speech: "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Lincoln’s second inaugural came just as the Civil War was drawing to a close. The weather was appropriately sullen. Days of rain and wind had left streets impassable with mud. A war-weary President ennobled the occasion with his inaugural address which many consider the greatest speech in American history. His second inaugural address is a somber, deeply-felt, and articulate meditation on the meaning of the Civil War to the soul of America. To those in the North who saw the war as a divinely-ordained crusade and who sought to exact retribution on the conquered enemy, he urged mercy tempered by understanding. Both sides, he reminded listeners, "read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully." The last paragraph is the most famous of any Presidential Inaugural speech: "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Congressional Luncheon

After the newly elected President has taken the oath of office and delivered the inaugural address, the President is escorted to Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol for the traditional inaugural luncheon, hosted by the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies (JCCIC).

While this tradition dates as far back as 1897, when the Senate committee on arrangements gave a luncheon for President McKinley and several other guests at the U.S. Capitol, it did not assume its current form until 1953 when the JCCIC began hosting a luncheon for the President, Vice President, Senate leaders, the JCCIC members, and other invited guests.

1981: Reagan’s Inauguration

In 1981, the inauguration of Ronald Reagan was moved to the west front of the Capitol, setting a new precedent that continues to this day. The west front location provides more space for spectators and a larger platform for dignitaries; but most of all, with its sweeping vista of the Mall, the west front is best suited for televising the event.

“True and Enduring Significance”

Writing in 1969, Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen summed up the significance of the inauguration ceremony and its Capitol connection:

“The vitality of our tripartite system of government, a coequal representation of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, is manifested by this ceremony taking place as it does on the steps of the Capitol with the House of Representatives on one side and the Senate on the other. . . . Because it quite properly belongs to the people, the ceremony traditionally takes place out of doors, in the midst of the people who are the real rulers of this great country and whose leaders and representatives exercise their authority ‘by the consent of the governed.’ This is the true and enduring significance of the Inaugural Ceremony to the American people.”

Learn More:

Paul F. Boller, Jr. Presidential Inaugurations: From George Washington’s Election to George W. Bush’s Gala. 2001

Louise Durbin. Inaugural Cavalcade. 1971.

Jim Bendat, Democracy’s Big Day 2005 Edition: The Inauguration of Our President, 2005.

Originally Published: 2009