By Christine Owen, USCHS Intern

Influenced by English landscaping in urban areas, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) dedicated his career to fostering, through his numerous landscape projects, a sense of order and tranquility in an increasingly urban and industrial American society. Reflecting on his work, Olmsted recalled: “The most interesting general fact of my life seems to me to be that it was not as a gardener, a florist, a botanist, or one in any way specially interested in plants and flowers, or specially susceptible to their beauty, that I was drawn to my work. The root of all my work has been an early respect for and enjoyment of scenery, and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to its power. I mean not so much grand or sensational scenery as scenery of a more domestic order — scenery which is to be looked upon contemplatively and is producing of musing moods.”

Olmsted, who was widely recognized as the father of American landscape architecture, became a progressive leader in his field in the second half of the nineteenth century. During his 53-year career, Olmsted created “green spaces” such as New York City’s Central Park as an oasis amid urban sprawl. His two-decade project on the grounds of the United States Capitol was distinct from much of the vast body of his work because he purposefully designed the Capitol grounds to accentuate the famous building.

In May 1873, Sen. Justin Morrill (R-VT) asked Olmsted to plan the grounds of the U.S. Capitol. Morrill, the chairman of the Senate Commission on Public Grounds, hoped Olmsted would “feel sufficient interest in this rather national project not to have it botched.” Olmsted already had earned a national reputation as a premiere landscape architect, having designed Central Park and the grounds of Stanford University. He also had some insight into how the government worked, having served as Secretary of the Civil War Sanitary Commission in Washington. Olmsted accepted the job, telling Morrill he felt the Capitol and its surroundings should help “form and train the tastes of the nation.”

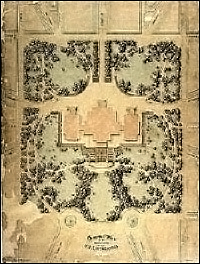

On June 23, 1874, Congress passed an act making Olmsted the first landscape architect of the United States Capitol. His original design envisioned a ground plan that united the White House, Capitol and other government agencies to symbolize the union of the nation. He scaled back his grand plans, however, being permitted to develop only the 50 acres then comprising the Capitol grounds.

In his previous projects, Olmsted had made architecture less important than its green surroundings. Central Park in New York City is a prime example. Throughout the park, the trees, plants, grass and lakes act as the main focus for park-goers and outdoor enthusiasts. Although there are many buildings on the 800-acre site, many of them are downplayed by the beautiful surroundings. However, for the seat of the legislative branch, Olmsted wanted to make the Capitol building the crowning centerpiece.

Olmsted envisioned an open setting immediately surrounding the Capitol and a more naturalistic scenery with shrubbery and trees further from the Capitol, nearer to its entrances. The creation of a coherent circulation system took most of the design process. The east side of the Capitol needed more open spaces for large masses of people during inaugurations and other big events then normally held at the East Front. Two large ovals with scattered trees were designed for the east side to accommodate the grounds during such events.

Because the grounds were only 50 acres, Olmsted could not make a park out of the surroundings of the Capitol. Twenty-one streets touched the Capitol grounds, with forty-six entrances for both pedestrians and carriages. These restrictions limited Olmsted’s options, but he finally created a picturesque scene that emphasized the Capitol’s beauty in places where the entire building could be seen.

From its inception Olmsted knew the Capitol project would be a huge task. He had first visited the Capitol in 1839 with his father. At that time, the grounds were in the process of a modest reconstruction — molding rectangular grassy areas surrounded by trees from the wild, chaotic wilderness which engulfed the beauty of the Capitol. The trees that were planted, however, stole the nutrients from the grounds and soon killed other forms of vegetation. Olmsted had to first resurrect the nutrients before any reorganization of the grounds could be made. He began by spending $60,000 to improve the soil, level the ground and add new sewer, gas and water systems. Olmsted soon realized that the costs would surpass the allotted budget, but he made no plans to inform the House Ways and Means Committee. His experience as the Secretary of the Sanitation Commission (which later became the American Red Cross), proved invaluable when it came to renewing funding for projects. At one point Olmsted ordered his laborers to slow down a phase of the project so they would not be near completion by the time winter came. This guaranteed another year of work on the Capitol, and more leeway on his projects.

For his original design of the grounds, Olmsted was paid only $1,500. He also was allotted money for travel expenses, salaries for his hired hands and a sizeable $200,000 budget for improvements to the Capitol grounds.

During his 18 years as the landscape architect of the Capitol, Olmsted worked to create a scene where the architectural triumph of the United States Capitol would be emphasized. While the natural beauty of the grounds would offer comfort and solace to visitors and city-goers, they would not supersede the views and sight-lines of the Capitol. If his other projects such as Central Park tried to foster orderliness and a cosmopolitan taste among the city masses, his design for the Capitol grounds imparted to Americans a sense of respect for the grandeur of their democratic republic.

Originally Published: 1999