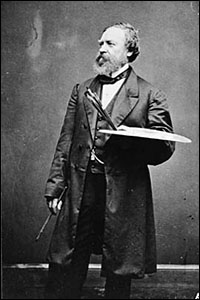

Armed with scalpels and girded with scaffolding, conservation technicians are busy uncovering the original splendor — unseen for generations — of Constantino Brumidi’s Capitol murals. Brumidi, an Italian artist, came to the Capitol in 1855 and during the course of a quarter century painted the Apotheosis of Washington on the Dome canopy, the Rotunda frieze and the Senate wing corridors. Brumidi had mastered the fresco technique and sculpture in Rome. After studying art there for 14 years, he painted murals in the Vatican Palace and at a nearby church called the Madonna dell’Archetto. When Brumidi participated as a captain of the civic guard in the Republican Revolution of 1848, however, his Italian career ended. Imprisoned and later exiled, he emmigrated to the United States in the early 1850s.

Brumidi, and the team of artists and painters whom he assembled, painted his murals in true fresco, drawing heavily from Pompeiian, ancient Roman and classical Baroque influences. Brumidi was known especially for depicting great Americans with allegorical Roman figures. His murals depict America’s founders, American Indians and other peoples of the Western Hemisphere — as one conservator has observed — with great “individuality and dignity.”

Brumidi’s ebullient personality and talent helped him to overcome resentment from American artists and the xenophobia of the 1850s. But while professional jealousy and contempt for foreigners did little to hurt Brumidi’s career, years of moisture, leaks, dust and (for nearly four decades) gas torchlight residue obscured the original splendor of his work.

Through as many as six periods of repainting, artists matched their restoration colors not to Brumidi’s original brights but to the dirty and yellowed colors of the unrestored murals. Passing judgment on his degraded and darkened works, many scholars assumed Brumidi to be an inferior artist. Consequently, by the 1950s even the man hired to restore Brumidi’s work on the canopy of the Dome believed the mural’s “chief qualities were architectural and historical” but not artistic. Thus, Allyn Cox had no problem recommending they be touched up, “even if it did involve more repainting than is considered ethical in the best museum practice.”

Curator of the Capitol Barbara Wolanin, in her recently published Constantino Brumidi: Artist of the Capitol, suggests that behind the layers of dirt, grime and over-paint that have obscured Brumidi’s work is hidden a new perspective on the artist himself “That’s what really motivated me to do this book — no one had really seen Brumidi; no one had really seen his work the way it should have been,” Wolanin told an audience in November 1998 at a lecture sponsored by the Society and the Library of Congress’s Center for the Book.

The restoration process has been divided into two major phases. In the late 1980s Bernard Rabin and a team of conservators restored Brumidi’s monumental work on the 4,664-square foot canopy of the Dome highlighted by the Apotheosis of Washington. The team also restored the 300-foot frieze (the artist’s last major work) just below it.

In the early 1990s, nationally renowned art conservator Christiana Cunningham-Adams initiated a study on the Brumidi Corridors in the Senate wing of the Capitol. Cunningham-Adams was convinced that Brumidi’s ornate panels were much darker than the artist had originally conceived and executed them. She used the scala method (a graduated exposure revealing paint layers step by step) which requires conservators literally to scrape off each layer of paint down to the original with a scalpel. When Cunningham-Adams opened “windows” (small areas of restored artwork) she confirmed her belief that the original murals had been dramatically altered by over-paint. For instance, the dark green borders that surround the wall panels had been over-painted as many as 15 times; many of the panels had been painted more than four times.”It’s a common phenomenon, Cunningham-Adams said. “When a layer of paint darkens and yellows with time, new layers of paint are added in an attempt to match the old. The change of palette can be quite dramatic; but what’s even more dramatic is the loss of artistic quality.

Cunningham-Adams and her husband George W. Adams developed a ten-year, multi-million dollar restoration project for the Brumidi Corridors. Approved by Congress and initiated in 1996, the program allows conservators to uncover Brumidi’s originals and preserve them. Old nicks, scratches and gouges are retouched with watercolors and surfaces are protected with a synthetic resin.

Cunningham-Adams’ work also advances the work of conservator Catherine S. Myers, whose research into Brumidi’s fresco technique was funded by a Society fellowship. Myers’s research and Cunningham-Adams’s restoration reveal that in the Brumidi Corridors, the original murals were executed in a rare lime-wash fresco technique: a sophisticated method of painting in which water-based pigments are absorbed in a wet lime surface. This method, whereby crystals formed by the lime reflect light, adds a luminous quality to the paintings and brightens the room.

Artist of the Capitol, which devotes several chapters to the restoration process, suggests — as Wolanin put it–that “just by getting up on the scaffolding and getting close to his work” we now know that Brumidi’s techniques were much more complex than previously thought.

“Brumidi did not just paint in true fresco but he combined all kinds of techniques: tempera by using glue to get a poster-paint effect, by using oils, by whatever techniques were going to get the effect that he wanted,” Wolanin said.

Brumidi also mastered an artistic effect that still awes visitors and tricks even those eyes familiar with the halls of the Capitol. Trompe l’oeil (the French for “fool the eye”) is a technique of creating effects of light, shade and perspective that make the image appear to be a three-dimensional sculpture. Brumidi often relied on it in to convince viewers that they were looking at carved frames or sculpted cherubs. Trompe l’oeil gives flat walls the appearance of depth and the illusion of greater space.

“This is the first time in 100 years that the original artwork painted by Brumidi and his assistants have been the way he saw them,” Cunningham-Adams said. “Rediscovering these frescoes is a moving experience for us all.