By Daniel Visnich

The California State Capitol, constructed between 1861 and 1874, features a 220-foot tall dome with striking similarities to the dome of the United States Capitol. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

More than a century after California became a state in 1850, Raymond Girvigian, FAIA, the restoration architect for the California Capitol, described the formative period for the location and building of the State Capitol as “the roving years.” The State House, whether in the form of a capitol or a saloon, moved frequently. The site of the first legislature was the pueblo of San Jose in 1850-51. Perhaps because of the poor lodgings and accommodations in San Jose the state legislators used the 40-foot by 60-foot adobe building and a home across from it for a saloon. The first legislature, not a particularly distinguished body, went down in history as “the Legislature of a Thousand Drinks.”

Former Mexican General Mariano Vallejo offered the new state more than 150 acres on San Pablo Bay and funds to construct public buildings, including a $125,000 capitol. The appreciative government promptly named the town Vallejo and moved to its uncompleted State House there for seven days. The next session met briefly in San Francisco on December 30, 1851, but within a month was back in Vallejo. Ever adaptable, the legislature used the basement floor as a saloon and a skittles alley. Nevertheless, the politicians found the work-in-progress government town miserable, with little food and few lodgings or other accommodations.

Sacramento, virtually created by the Gold Rush of 1849, was a hustling port town in 1852, larger than any other around, including San Francisco. Business thrived and the streets bustled from early morning until late at night, full of wagons and pack trains loading goods for the mines. John Breuner, a Sacramento furniture maker, was reputed to have started his career building cradles for the miners and had a thriving business building sturdy beds. He would go on to make 120 beautiful carved walnut desks for the state legislature.

Sacramento was an exciting place, and the legislature decided in January 1852 to meet there temporarily while Vallejo was completed. The legislative session continued until March, when the city was flooded and the legislature paddled back to San Francisco.

Conditions in Vallejo had improved very little by the following year. On the other hand, Benicia, an early whaling port and later a deepwater port for the high-speed clipper ships, had a population of 1,000. All manner of ocean-going ships and river craft docked at its well-protected inland wharves. Former American Consul Thomas O. Larkin, a member of the state constitutional convention at Monterey and then a state senator, saw to it that the federal government made Benicia the state’s ordnance depot and records center. He speculated with General Vallejo that it would be the state’s leading city with the greatest harbor on the Pacific Coast, far superior to flea-infested San Francisco. The legislature met at Benicia’s City Hall in February 1853. Still, the town was too small for those who wanted the good times and winsome creature comforts of Sacramento.

For those who would make their fortunes directly or indirectly from gold mining, Sacramento was more than a day’s travel closer to the mines than the other nearest potential capital, and it was also a port. Furthermore, it was already building the first railroad west of the Mississippi, running between the river docks of Sutterville (now a part of metropolitan Sacramento) and the town of Folsom, which was located close to the gold mines.

The interior of the dome of the California State Capitol is seen here after the historic restoration of the capitol, 1976-1982. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

Sacramento’s town fathers, already doing quite well providing services to the miners, made an offer that the legislature couldn’t refuse. Sacramento would provide the use of the county courthouse without charge, along with other suitable offices for state officials. The city would move the legislature and its furnishings from Benicia by steamboat for free. Moreover, it would provide a building site for a permanent capitol in the center of town. The 1854 session began using the Sacramento County Courthouse as the new capitol.

That very same year, however, the courthouse was destroyed by a fire, during which a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington hanging in the Senate chamber was saved by the governor’s exhortations to the senators to risk their lives and rush into the burning building (reminiscent of Dolley Madison’s rescue of the White House portrait of Washington during the War of 1812). Undaunted, the city and county built a new, even more handsome courthouse, which was completed in time for the opening of the 1855 legislature. During the years from 1856 to 1860, the question of changing the capital to San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose, and even Santa Cruz arose, but legislation introduced on behalf of these cities was never enacted.

In 1856, the legislature passed a law authorizing a tax to construct a capitol on Sacramento’s public square, the present Cesar Chavez Plaza fronting City Hall. The legislature accepted a plan submitted by Reuben Clark, a former carpenter from Maine, who had worked on the Mississippi State Capitol twenty years earlier. Clark’s plan called for a two-story structure, with basement, in the form of a Greek cross. The building was to have Corinthian-style columns with a rotunda under its dome. The first-story exterior masonry walls were to be veneered with granite ashlar; the walls above were to be coated with mastic. The State Supreme Court, however, ruled against the taxation method enacted to finance the construction and the project was abandoned. Its brick foundation still is buried in the plaza.

During the 1860 session, the legislature passed another bill at the urging of Gov. John Downey, designating a new site for a permanent capitol three blocks south of the plaza. The law authorized $500,000 for the construction, provided that the city paid for the land. Miner Frederick Butler won a competition over six other architects for the job. Although a newly formed Board of Capitol Commissioners selected the plans of Butler, who had earlier designed Sacramento’s State Agricultural Hall, critics pointed out that it was astonishingly similar to the 1856 Clark plan. As it turned out, Clark had been on Butler’s payroll at the time he made those plans. As a result, Butler was awarded $1,500 for the design and Clark was appointed the Capitol’s superintending architect.

There was no general contractor for the entire project, nor was there ever a completed set of working drawings from which to build. Thus, from 1860 to 1874, each succeeding architect drew plans that influenced and even altered the course of the design.

Construction began in 1860, when workers dug excavation trenches and laid a bed of cobblestones and broken granite, pouring a three-foot thick stratum of concrete over it. On May 15, 1861, five days before the legislature adjourned, officials laid a cornerstone before a large crowd that watched the ritualistic Masonic ceremony.

The Capitol’s foundation work continued, but drenching rains that December flooded the excavation, ruining the groundwork. Another deluge devastated the city when the legislature met on January 6, 1862, and revived talk of moving the Capitol. Four days later, Leland Stanford climbed into a boat from a second-floor window of his home and rowed the eight blocks to the courthouse cum capitol to be sworn in as governor. Two weeks later, the legislature, unable to do business in the lingering mud, moved to San Francisco for the remainder of the four-month session.

As governor, Stanford saw to it that California remained in the Union, that the Central Pacific Railroad (which he headed) broke ground, and that Reuben Clark, the Maine native, continued as California’s capitol architect. Because of the war, Clark was now cut off from building materials ordered from the East Coast, such as cast iron from the Phoenix Iron Works of Philadelphia, which supplied the iron beams for the U.S. Capitol. Nevertheless, Governor Stanford cajoled Clark to get on with the work despite the war (just as construction on the U.S. Capitol continued relatively unabated during the war).

The richly decorated restored Senate Chamber of the California State Capitol provides a window into the nineteenth-century, when a guest at the 1869 opening described the room as “rich, tasty and substantial.” (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

The legislature passed two bills in 1863 that affected the construction: the first created a special Capitol construction fund and the second required the Capitol Commission to award contracts for labor and materials by the day. These two acts made certain the construction would drag on piecemeal, with the help of winter rains, for another eleven years. Governor Stanford perceived the delay and, in his annual message to the legislature in December 1863, he pointed out the inevitable dangers. Stanford was, however, addressing a legislature dominated by thoroughly divided pro- and anti-slavery Democrats who were more than happy to have him take the heat for delays not of his own making.

With the foundations ruined by winter rains and Clark’s working drawings spoiled by the flood, the governor, in his role as head of the Capitol Commission, made regular rounds of encouragement to the architect’s office, and had Clark redraw the plans to increase the foundation height by six feet. Due to such political pressures from the governor, the legislature, and the commission, Clark wrested the rise of the west front walls faster than the sides and back, providing a Potemkin-like appearance of progress. The rest of the city also started raising itself by anywhere from ten to twelve feet to provide some sort of protection from future floods that were almost certain to come.

During the ensuing years, the Capitol Commission became more critical of the slow, plodding progress; in turn, Clark carped at the construction crew. In a turnabout, some of the mechanics claimed Clark was a southern sympathizer, citing his work on the Mississippi State Capitol as evidence. The pressures of innuendo and clamor about his alleged treasonous actions got to the point that Clark took leave from his job. The Sacramento Union League Executive Committee charged Clark with being disloyal to the Union on May 4, 1865. He was accused of hiring “known secessionists” and supposedly was overheard saying that he didn’t care which side won the Civil War.

The first layer of granite ashlar above ground was completed before work stopped due to drenching winter rains. With the arrival of spring, work plodded along, and, by 1865, stone masons completed the granite ashlar up to the first-story cornice. Thus ended the first phase of the project.

Still, the accusations and sniping continued. Clark suffered a mental breakdown and was hauled off to the Stockton Insane Asylum. He died there on July 4, 1868, and shortly thereafter was posthumously exonerated by expert witnesses.

Clark’s assistant, Gordon Cummings, took over as acting capitol architect and reported to the Capitol Commission that Clark’s plan of using granite on the entire exterior would cost over $1 million. Cummings provided various cost-cutting alternatives. One was to cover the brick above the first story with mastic and use cast-iron decorative detailing. He estimated this work, painted to simulate granite, would cost $819,000.

In December, however, the Sacramento Daily Union strongly urged that the Capitol be completely veneered in granite, arguing against using cast-iron ornamentation and against plastering over the brick above the first story. The politically active stone masons may have hoped that the Capitol Commission would reconsider Cummings’s determination to use cast iron. The 1869 commission, headed by Gov. Frederick Low, ignored anonymous letters written against the architect and endured a strike by stone cutters, who charged that Cummings was incompetent. In January 1867, however, the Capitol Commission decided to complete only the first story in granite and cover the remaining brick walls with mastic, clad with cast-iron facades, names, and ornamentation.

The California Senate’s forty members sit at original ornate walnut desks crafted in 1869 by John Breuner, Sacramento’s leading custom furniture maker. The desks have been faithfully restored by reference to period photographs. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

In November 1866, a crack materialized at the center of the basement wall that caused an outcry by various politicians and the press, generating much unfavorable publicity. The Capitol Commission suspended work while an officer from the Army Corps of Engineers camp at Alcatraz and San Francisco architect Henry Kenitzer investigated. The crack was believed to be caused by the front substructure wall sinking as a result of unequal loads on the foundations. An examination found that the foundation walls were not wide enough to handle the temporary and unequal stress. The remedy, the two investigators claimed, was to construct huge brick buttresses beneath the west front and north walls to resist stress until the other walls were raised to equalize the weight on the foundations. This finding was a bonanza for the brick layers and brickyard owners but not for the stone masons, who desired an all granite ashlar capitol.

Hurling verbal brickbats, a group of stonecutters presented charges against architect Cummings, but the Capitol Commission cleared him. In the meantime, brick masons and brick makers worked furiously, installing vast amounts of money in the form of brick buttresses, which connected in no way with any other structures. A little more than a century later, Lloyd Lee, a structural engineer with the Capitol Restoration Project (1975-81) confirmed that the buttresses did not structurally support the foundations. They simply formed a hidden repository, a veritable political construction coverup. During the next two years of construction, the crack did not widen, nor did further cracks occur.

A united Democratic party swept the state elections in September 1867. Henry Haight was elected governor. This result meant a change in the Capitol Commission, consisting of the governor, secretary of state and state treasurer, serving with two citizens.

In January 1868, the state legislature, motivated by construction problems, fear of floods, slow progress, and, last but not least, politics, introduced bills to remove the Capitol to San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland, or Benicia. As a result, the legislature held another investigation in 1868 but it, too, found the building to be stable and safe.

Cummings continued the work, and by January 1869, the structure’s interior was almost completed. By November, the Capitol was nearly ready for occupancy, despite the fact that interior and exterior detail work remained to be completed. More than $1 million had been expended and it was expected that it would take another $500,000 to complete the building.

To keep the plumbing trades, both tradesmen and their bosses, happy and properly disposed politically, a great deal of plumbing was installed. It was noted during repairs later that most of this plumbing went from nowhere to nowhere else, and didn’t connect with much of anything in between, but it did a splendid job of providing employment and filling yawning spaces underneath various floors.

Little expense was spared in the interior decoration. The doors in the first-floor corridor were of black walnut with laurel paneling and bronze hinges. The huge windows, of the finest Belgian glass that was transported around Cape Horn, had folding shutters that tucked into interior pockets. By November, Cummings was preparing working drawings for the west front and north and south porticos and terraced grounds leading up to the building, as well as for the dome.

On November 26, 1869, Governor Haight, Secretary of State R.L. Nichols and Treasurer Antonio F. Corone–the Democratic Capitol Commissioners–opened their offices in the partially completed building. The State Supreme Court beat the legislature’s first session in the new Capitol by days, moving into their chambers on the basement floor.

The Supreme Court met in its apse court room for the first time on December 3. Approximately a week and a half later, a grand ball was held for state officials and legislators in the corridors, halls, legislative chambers, and rotunda area to celebrate the occupancy of the new, albeit unfinished, building. Several hundred persons attended, dancing quadrilles under gaslights in the Senate Chamber and “fancy dances of the day” in the Assembly Chamber. At midnight, supper was served in the long first-floor corridors and the dancing continued until the early morning hours. The participants praised the interior appearance and the furnishings as “rich, tasteful and substantial.”

Thus ended fifteen years of transient lodging in two Sacramento courthouses. California could finally call attention to its own symbol of democracy, the Capitol–the dome of which “rose splendidly on the plain.”

Cast Iron Taken For Granite?

Hues of green and gold unify the Victorian neoclassic Assembly Chamber of the California State Capitol. The gold motto inscribed above the dais reads: “Legislatorum est Justas leges condere” (the legislator’s duty is to make just laws). The Wilton weave carpet is by the same manufacturer as the carpet of the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

The Civil War shortage of materials created a new cast-iron industry on the West Coast, composed of inexperienced firms with limited facilities that nonetheless produced a superior product. The Miners Foundry of San Francisco, for example, produced for the State Capitol perhaps the tallest and, arguably, the strongest cast-iron columns in the country. A newly -invented steam tractor wagon was shipped by boat from San Francisco to haul the many columns from the waterfront to the Capitol in March 1870. Bystanders were impressed by the sight of the 30-foot long cast iron shafts–three feet longer than the U.S. Capitol dome’s peristyle columns.

The original 1861 architectural documents, located in the State Archives, do show exterior elevations with granite, windows, pilasters, base, and cornice. The columns are coupled, fluted, and with modified Roman Doric capitals and bases. Flat arches are flanked by two smaller semicircular arches, decorated with a prominent keystone. The first floor specifications include the use of granite ashlar–all of a uniform color–for the walls, eight fluted columns, window jambs, doors, steps and lintels. At this time, cast-iron columns and ornamentation were to be used in the interior only.

So what happened? Were the stonecutters irked because the Capitol Commission and Clark and Cummings failed to follow through with the complete use of granite ornament? As a result of changing stone quarries in 1864, the stone color changed.

In 1864, the state switched railroads that transported the granite. This, in turn, changed the quarries that supplied the stone, resulting in mismatched colors. The Sacramento Valley Railroad had hauled granite from a Folsom quarry to Sacramento since 1861. The Sacramento Daily Union, however, claimed that the state paid twice as much as what the railroad charged to transport granite to San Francisco–more than three times the distance. The competing Central Pacific Railroad came up with an offer: former Governor Stanford took Clark to the railroad quarry and showed him a superior stone to complete the Capitol. The railroad would permit Capitol stonecutters to use the granite at no cost and transport it free of charge.

Capitol Architect Clark, therefore, supported a bill to aid the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad, which in return would “transport and convey . . . materials for the construction of the State Capitol Building.” Furthermore, the railroad provided a stone quarry on the railroad line for whatever the capitol building required, gratis. The bill was signed by Governor Low on April 4, 1864.

Mismatched granite on the lower floor is clearly seen in viewing the west front piers. Raymond Girvigian, the Capitol’s restoration architect during the 1970s, thought that the stone masons probably expected that the grand staircase would cover up those areas–which it did not. Or, perhaps the mismatching of stone colors was their method to overturn any decision by the governor and his commission not to install the staircase. If this was a subversive ploy by the workers to outwit the governor, they failed in their cover-up attempt.

Unlike the Doric granite façade, the cast-iron ornamentation for the columns, windows, cornices, balusters, and architraves were patterned after the Roman Temple of Jupiter, according to Girvigian. The 1870s saw the completion of the exterior and site improvements. The interiors were essentially completed except for some rooms on the third floor. The basement was unoccupied and hermetically sealed. The dome had not yet been completed. The grounds were in a state of gestation; no permanent walks or drives were yet installed.

To complete the work, the property tax method of raising small sums, a method which prolonged the project, was finally tossed out. Two hundred fifty thousand dollars worth of bonds were issued for construction and site work. Now that the legislature actually occupied the building, members wanted the work done more quickly. The Democratic Capitol Commission, who previously jettisoned Cummings as superintending architect, now chose architects Henry Kenitzer and A.A. Bennett to resume the job, ignoring written protests from Cummings. Kenitzer, who had earlier worked with Clark in San Francisco, had been outspoken in his criticism of the foundation crack in testimony before a legislative committee hearing.

It appears that the stone cutters, who had waged war adamantly against Cummings, finally won more stone work from Kenitzer and Bennett. The new architects submitted a very dubious report to a receptive Capitol Commission, claiming that the building had again subsided, causing cracks, and throwing the west front arcade granite piers out of kilter. With this report accepted at face value by the Capitol Commission, which should have known better, the architects dismantled much granite work and tore out the brick arches of the west front portico, creating more work for both bricklayers and stone cutters. All that industrious and expensive make-work activity changed no measurements other than the financial.

The stone cutters’ victory was fleeting, however. Kenitzer and Bennett discarded Clark’s plan for a twenty-five-foot high granite exterior staircase to the main, or second, floor, mirroring the U.S. Capitol’s east front steps. The architects, who ripped out sound structure, now claimed in a strange rationale that the inclusion of the granite stairs would be “heavy, costly and useless.” Rejecting the steps, they argued, would permit light into the basement of the rotunda–which was never done during their time–and give the edifice “more lofty and graceful proportions.”

The architectural decision to scrap the grand stair entrance changed the total focal point of the capitol. The stairs would have led to the piano nobile, into the magnificent tiled foyer leading to the rotunda balcony, and thence to commemorative, mosaic-laid corridors that led to the legislative chambers. With easier access to the basement floor, the attention was now focused on the executive branch of government, particularly the governor, whose primary entrance would have been the Senate portico. Presumably the architect took this action at the behest of the commissioners whose constitutional offices were located on the lower floor.

Governor Haight and his fellow commissioners heard no complaints from the stone cutters. Under their policy, the construction crew worked an eight-hour day–somewhat unheard of during that century–and were paid double time for every hour over that period. According to later testimony, many workers put in a sixteen-hour day and therefore were paid for three days’ work. Bennett explained at a hearing that there was “a good deal of night work” without a watchman present and admitted he had no knowledge whether the workers’ hours listed on the payrolls were correct.

Kenitzer and Bennett charged that former architect Cummings had altered and modified the building design style, inside and out, from the Roman to the Grecian. The pair then proposed to immediately construct the upper part of the dome and place a golden ball atop the cupola instead of the statue depicted in Clark’s original rendering. The statue which Clark had envisioned was a bronze reproduction of California, inspired by the gold rush and completed by American sculptor Hiram Powers in 1858. In her left hand, the figure holds a divining rod before her loins, while her right hand is behind her back, holding a cluster of thorns, an allusion to the “deceitfulness of riches.”

The third floor, now completed and containing legislative committee hearing rooms, was reached by four flights of stairs. The most impressive of these was a pair of monumental stairs leading from the west front portico entrance, created by P.W. Burnett, a master builder from western Massachusetts.

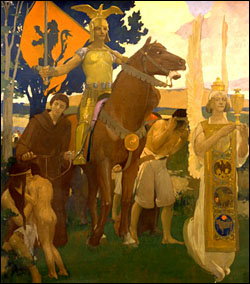

“Adventure,” a panel in Arthur F. Mathews’s 1914 mural depicting The History of California, originally placed in the first floor rotunda, is now located in the basement rotunda. The artist described this panel as depicting the arrival of European settlers, here idealized as a Knight Errant and priest, and their interaction with California’s native peoples. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

In 1871, the Capitol Commission authorized Pietro Mezzara, the putative first sculptor of California, to execute statuary for the west front pediment tympanum, with these works to be cast in art stone. The central figure was an eleven-foot high Eureka with a bear at her feet, and figures of Justice and Mining on the left, with Education, Art, Science, and Commerce on the right. On September 3, 1872 the sculptor was again commissioned to create clay models for cast stone statuary groups.

On December 19, 1871, the newly constituted Capitol Commission fired Bennett and Kenitzer. All of the construction workers were let go the next day. The commissioners more than suspected shoddy management of the project, including kiting and manipulation of building contracts, as well as the contractors skimming funds from the workers’ payroll vouchers. To clean up what it saw as a mess, the commission appointed Philetus W. Burnett as construction superintendent and directed him to hire a new crew. Not only was he a master builder and craftsman, but he was a respected businessman in the capital and the founder of Sacramento’s still-extant Burnett and Sons Lumber and Planing Mill.

Several months after P. W. Burnett was brought in, Cummings made a comeback in the new Republican administration. He was rehired as Capitol architect on May 18, 1872. Cummings “assumed charge of the work, by our order, and has discharged his duties faithfully and ably,” stated the Republican commissioners. The newly returned architect’s critique to the commission that November summarized the progress since his last report, four years earlier. Cummings could not resist criticizing the work done in the intervening years by Kenitzer and Bennett, who had similarly taken shots at his earlier work.

The cast-iron columns of the north and south porticos had been hoisted by a derrick and set with their elaborate Corinthian capitals. Granite steps were installed at the first story basement entrances and stone work completed. The original roof gutters of lead had been replaced with copper “without much improvement,” he wrote. Cummings also took to task the plumbing system that had replaced his work. He castigated the previous architects for its expense, faulty construction, and inability to be maintained because of very poor access. Due to dwindling funds occasioned by boodle, pelf, and peculation during the Haight administration, the Capitol Commission postponed work on January 15, 1873, after the sculptures were secured to the pediment.

When work resumed six months later, black and white marble tile from Vermont and New York were laid in the first floor rotunda and the outside porticos, first and second floors. Maw geometric tile was laid on the second floor rotunda, similar to the design at the Smithsonian Castle. Cummings completed the roof balustrades by substituting Ransome cast stone for the intended cast iron used at the porticos and elsewhere, claiming it would save money. He ended the 1873 work indicating he wanted to paint the natural copper dome white and place the bronze figure of California by Powers atop the cupola. He was to do neither.

By February 1874, the work was completed inside and nearly finished on the exterior. A temporary picket fence was installed until it could be replaced by an ornate cast-iron design by Cummings, coupled to six pair of granite entrance posts surrounding the Capitol grounds. The cast-iron posts were ornamented with bears’ heads and terminated with acorn tops. Gaslight lamp posts were placed at the terrace steps.

The actual completion of the Capitol went unnoticed. The February 1874 Minutes of the Capitol Commission simply reported that the statuary was in place, the large derrick stripped and its rigging housed, construction workers discharged, and the architect suspended, receiving his last paycheck February 8. In any event, the grounds were incomplete and remained unimproved for the next several years.

Later Developments

Larkin Goldsmith Mead’s Columbus’ Last Appeal to Queen Isabella was purchased from Mr. and Mrs. Legrand Lockwood by pioneer banker Darius Ogden Mills for $30,000, who then presented it the state in 1883. Slightly over life size, the sculpture weighs approximately nine tons including the base and is located in the California State Capitol Museum. (Courtesy California State Capitol Museum, California State Legislature)

In 1881, massive Rocklin granite gate posts, weighing sixteen tons each, were installed at each entrance and the cast-iron fence was set in place. In 1883, a statute of Columbus addressing Queen Isabella, executed by Larkin Goldsmith Mead (whose brother was the anchor man of the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White), arrived from Florence, Italy. Two years later, Governor Stoneman, in his annual message to the legislature, requested $7,000 to complete the Capitol’s cast-iron fence and a sidewalk around the Capitol.

The Capitol came into the electric age when, in 1895, Sacramento became the first city in the world to bring in electricity from a remote generating site by high-tension, high-voltage transmission. In anticipation of the event, electrical wiring had either replaced or was run through gas lighting lines, so that each room had at least one electric light and a plug, usually suspended from the ceiling. Wires then dangled down, often obliquely, to desks below to provide power to various table lamps. Other power-consuming accessories and status symbols would come along later. In 1896, encaustic tiles made by the Mosaic Tile Company of Zanesville, Ohio, were installed in the first floor corridors, with four large Minerva murals at the north and south entrances, as well as entering the rotunda, with its black and white marble tile.

The beginning of the twentieth century was one of tumultuous change for the Capitol. In 1905, the San Francisco architectural firm of Sutton and Weeks completed plans to alter the interior for more space. The west front monumental stairs were removed for that purpose, the chambers were remodeled, a new marble foyer was created, two elevators were added, and a fourth floor was created by replacing the old timber roof with a new higher, steel-framed one. On the exterior, all but four of the statues on the roof were removed and the balustrade was replaced with a solid brick panel. This was the first, but not by any means the last, major alteration to the Capitol.

By the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, pressure was building for an extension to expand facilities for the growing state government. A two-block site in front of the Capitol was acquired, and Sutton and Weeks was again chosen for the work in 1918. Two new Capitol buildings were completed in 1928. The state library and the courts were moved out of the older, historic area of the Capitol proper, and into the Library and Courts Building. During the Great Depression years, there were changes in the governor’s suite, which was then located in the southwest corner of the Capitol. The offices were expanded from there to the rotunda and mezzanines were added. As a result, the rich ornamental ceiling and other splendid and magnificent architectural details were destroyed.

During the post-World War II era, the annex idea, in vogue throughout the nation, hit California as well. The block mass, neo-fascist annex was added, destroying the Capitol’s finest architectural feature, the East Apse, where the Supreme Court and State Library formerly were located. For the first time in its history, the Capitol exterior was substantially changed. The interior stairs of the rotunda were also removed and replaced. The last four figures of sculpture were removed from the roof, the terraces of the grounds below were removed, and the nineteenth-century granite steps and gateposts, along with the ornamental cast-iron fence, were abandoned.

Daniel Visnich has been actively involved with the California State Capitol for many years. He was executive director of the California Capitol Historic Preservation Society and executive officer of the Historic State Capitol Commission. This article is drawn from his paper presented to the U.S. Capitol Historical Society’s conference on state capitols in 2000.