During the COVID-19 global pandemic, flexible schedules became the norm at many workplaces as many people now increasingly work from home. While there are benefits to this change, many American workers still feel overworked, especially as the division between home and the office is muddled by technology. As a result, there is rising interest among companies, members of the workforce, and elected officials to redesign the structure of American labor—including the potential adoption of a four-day work week. As society grapples with a possible transition, it’s interesting to consider Congress’ historic role in labor issues and the circumstances that led to the current five-day, 8-hour work week.

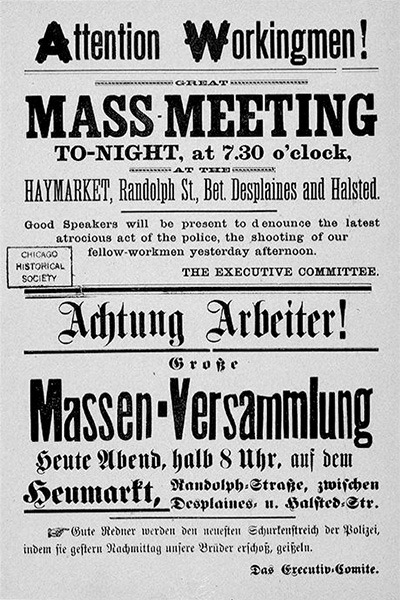

During the 19th century, American labor movements such as the National Labor Union and the Knights of Labor helped unite workers and raise public awareness to the need for an eight-hour work day. At this time, it was not uncommon for laborers to work 100-hour weeks. In the 1860s, workers began to strike in support of shorter work hours. Although President Ulysses S. Grant responded to these demonstrations by mandating an eight-hour work day for government employees, few other industries and state leaders joined him. The National Labor Union fought for the widespread adoption of an eight-hour workday, but failed in its appeal to Congress. It was then that the Knights of Labor—which grew to more than 700,000 laborers—began their efforts to peacefully advocate for legislative reform. Violent labor protests, however, also became common during this era (for instance, the Haymarket Riot). Finally, Congress responded to these demonstrations and pervasive labor strikes in the railroad industry when it passed the Adamson Act in 1917. The bill established an eight-hour workday for railroad workers and required that they be paid overtime beyond those hours. President Woodrow Wilson signed the Act into law, in hopes that it would end the strikes.

Later, in June 1933, Congress enacted the National Industrial Recovery Act in the wake of the Great Depression. This unprecedented Act set maximum work hours and granted workers the right to organize, set fixed wages, and gave laborers the right to collective bargaining, in addition to other privileges. However, the Act was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935. The case, Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, found that Congress, as a part of the legislative branch, did not have the Constitutional authority to grant the President the right to control industry through these reforms. In response, the Wagner Act was passed that same year. While it still did not directly address work hours, the Wagner Act did reaffirm workers’ rights to unionize and engage in collective bargaining.

In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which marked the culmination of decades of labor legislation and advocacy. This sweeping measure officially established the 40-hour work week across industries, set a minimum wage, and made child labor illegal. The Act was amended in 1949 to raise the minimum wage from 40 cents to 75 cents per hour. And since then, the Act has been amended many times, including in 1955, 1961, 1966, 1974, 1977, 1985, 1986, and 1989. While the amendments focus on different areas, they generally work to expand the coverage of the Fair Labor Standards Act and raise the minimum wage.

But just as there are advocates for a four-day workweek, there are those who’ve voiced concerns about a potential change. Client-centered businesses, for instance, find the model more difficult to implement, as they need to be widely available to satisfy clients’ needs throughout the whole week. Additionally, companies can only shorten their workweek if they are willing to shorten their overall work hours; if extra hours need to be crammed into four days of work instead of five, all of the benefits of the change are lost. There are also employees who want to work extra hours for overtime pay. Will that still be available? And if companies do offer employees overtime to work similar hours as before, a four-day work week could cost some companies more than it saves.

While Congress has not yet made significant movement in support of a shorter work week, it has at least discussed possible changes. In 1965, a Senate subcommittee concluded that, by the year 2000, the average American would only work 14 hours per week and have access to seven weeks of vacation each year. This prediction was incorrect to say the least. It reveals, however, the longstanding awareness among leaders that work hours should evolve as the economy does. This past July, California Congressman Mark Takano introduced legislation that would effectively shorten the work week from five 8-hour days to four. Specifically, his bill would mandate non-exempt workers to be paid overtime after they work 32 hours in a week. Some employees would work less under Rep. Takano’s plan that would amend the Fair Labor Standard Act. Others, though, would work the same hours, but for greater compensation.

If there is a future change in the U.S. work schedule, it will likely first need to gain traction with individual companies and advocacy groups before it can be successfully integrated into legislation. There is no doubt that any such proposal will generate heated debate about the role of government in regulating private business. But someday, it is possible that Congress will debate legislation that mandates a four-day work week and whether such legislation is in the best interest of American workers and a productive economy.

Written by guest contributor Maeve Silk, a student at Georgetown University studying history and English and minoring in art history. Edited by U.S. Capitol Historical Society staff.

Sources:

https://www.kuow.org/stories/32-hour-workweek-proposal

https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/august-20/

https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=66

https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/who-we-are/our-history/1935-passage-of-the-wagner-act

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/about/history

https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-the-40-hour-workweek-2015-10

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/08/where-the-five-day-workweek-came-from/378870/

https://money.cnn.com/2013/07/09/news/economy/shorter-work-week/

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/06/four-day-workweek/619222/