On June 19th, 1865, over 250,000 enslaved people in Galveston, Texas received news of their emancipation, marking a significant milestone in American history. This pivotal event commemorated the birth of Black Independence Day, a celebration embraced by African Americans across the nation.

Following the end of the Civil War, Juneteenth celebrations emerged as a tradition among formerly enslaved individuals and their families. These celebrations initially took place in Texas but spread to other states where Black communities resided. Activities during the festivities included religious services, storytelling, singing, games, and BBQs. A significant tradition was the symbolic act of discarding the garments worn during enslavement into a river, representing a visual separation from bondage. It experienced a resurgence during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. However, the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2020 brought national attention to Juneteenth’s significance. The widespread support for recognizing Juneteenth stems from the acknowledgment that it represents America as a nation deeply committed to principles of human freedom and equality.

On June 17, 2021 President Joe Biden signed, with Members of Congress, the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act at the White House. (Evan Vucci/AP)

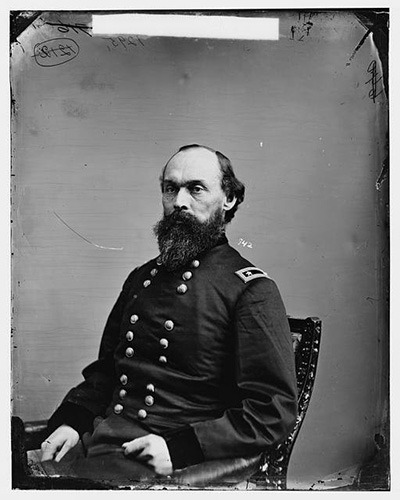

Recognizing Juneteenth as a federal holiday also gives Americans the opportunity to contemplate the complicated processes of emancipation that took place after President Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. Specifically, Juneteenth marks the day (June 19, 1865) when a Union Army general, Gordon Granger, arrived in Galveston, Texas, and demanded that the state’s 250,000 plus enslaved people be set free.

(Library of Congress)

To communicate this demand, Granger read aloud General Order No. 3:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.

In other words, enslaved people in Galveston, Texas did not know about Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation until this Union army general arrived two and a half years later and announced it to the public. A delayed awareness of the Emancipation Proclamation was the reality for many enslaved people in the South. It was not until the Union Army swept through the South in 1863 and 1864 that news of the Proclamation spread—and populations of enslaved people across the South were able to celebrate their freedom. Only the action of Congress to pass the 13th Amendment and the ratification by the necessary number of states on December 6, 1865, officially abolished slavery in every state, not just those in open rebellion.

However, slavery lingered in the South because many in the former Confederacy resisted paying the newly freed people. Erin Stewart Mauldin, a professor of history at the University of South Florida-St. Petersburg observes that “though slavery ends, the conditions for many change very little initially.” As such, the struggle for freedom evolved into a serious struggle for economic independence. Remembering emancipation and all of its complexities—its successes and its shortcomings—is key for working towards equity and equal rights today. Mauldin believes that a nationwide recognition of Juneteenth is crucial:

It is immensely important to remember the difficulties of fighting and securing even the smallest measures of freedom … Juneteenth has become a symbol for emancipation and provides a highly visible celebration that does get at these difficult conversations of America’s racial history.

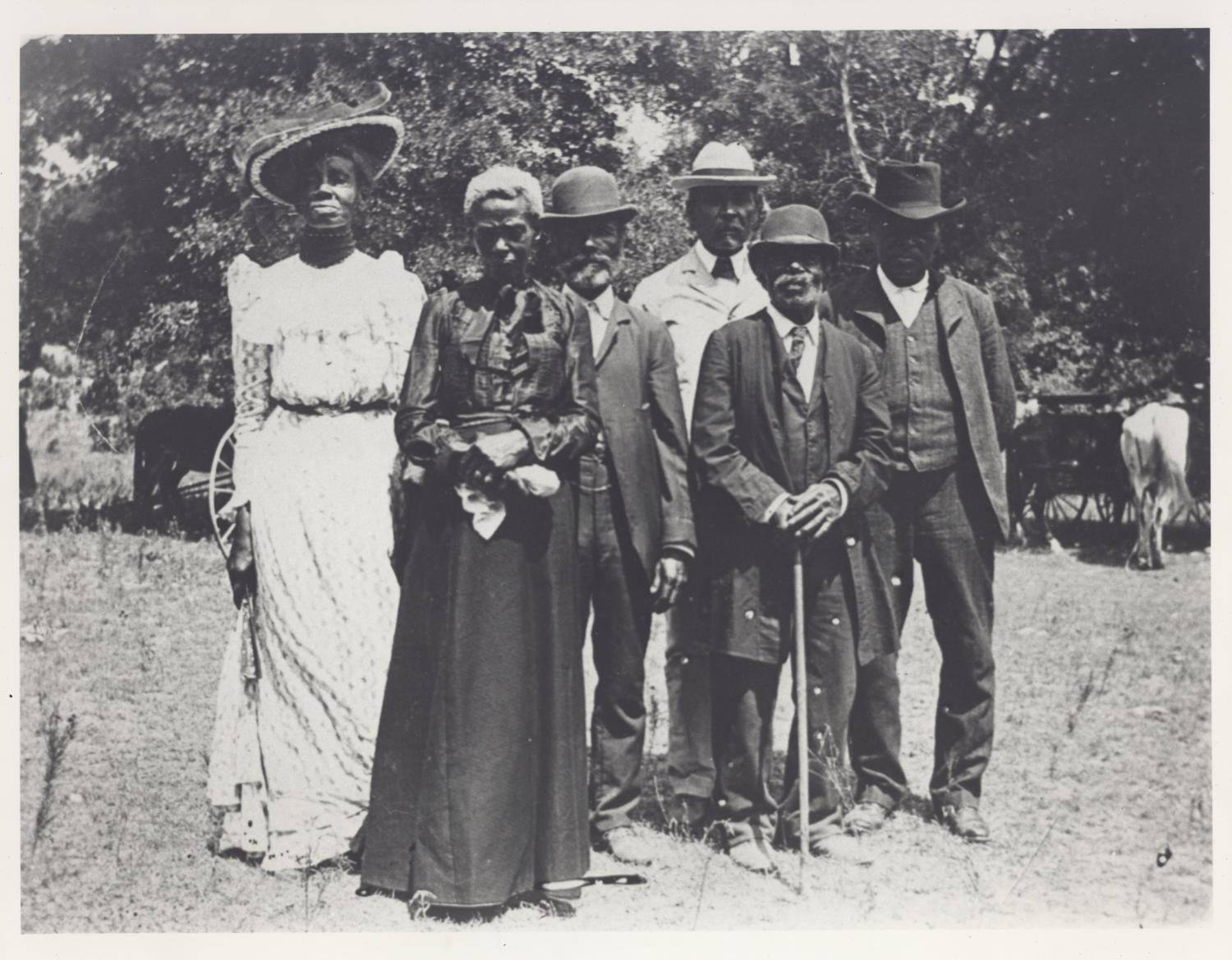

But Juneteenth is not just about building historical awareness and self-education. It is also clearly a holiday for Black Americans. It was only a year after the events at Galveston that formerly enslaved Black people and their families began gathering and celebrating their freedom. This tradition began in Texas, but quickly spread to other Southern states like Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Alabama, Florida, and California. These celebrations involved religious services, oral story-telling events, singing, and games, and often centered around eating—like at a barbeque. Another common tradition involved dressing up, which was particularly important because many enslaved people in America were strictly prohibited from wearing clothes besides the rags they were given. At these early Juneteenth celebrations, formerly enslaved people ceremoniously tossed their rags into the river, and put on clothes they stole from their former slave owners. Historically, then, Juneteenth is a holiday for formerly enslaved Black Americans and their descendants to celebrate their freedom through acts of symbolic resistance against American white supremacy.

While celebrations of Juneteenth go back to 1866, the effort to make Juneteenth a federal holiday is fairly recent. Juneteenth celebrations revived during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. But it was only last year that U.S. Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas) pushed for federal recognition during the height of that summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.

The bill didn’t make it through Congress, but this year proved different. Representative Jackson Lee responded thusly:

I think Juneteenth tells a wonderful story. It’s a story of freedom. It happened two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, but it still set a pathway of freedom. Who are we as a nation, if you’re frightened about freedom and liberation and joy?

While Juneteenth doesn’t eliminate structural racism in America, recognizing it as a federal holiday is a crucial step towards bringing the rich history of Black Americans into the center of both our history and identity.

Written by guest contributor Anna Biesecker-Mast, a student at the University of Dayton studying History and English; and minoring in Religious Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies. Edited by U.S. Capitol Historical Society staff.

Sources:

https://juneteenth.com/history/

https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-juneteenth-and-why-is-it-celebrated-2834603

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/16/1007340587/house-passes-a-bill-to-commemorate-juneteenth-as-a-federal-holiday

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/15/us/politics/juneteenth-federal-holiday-senate.html

https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/13th-amendment