Shirley Chisholm

(1924-2005)

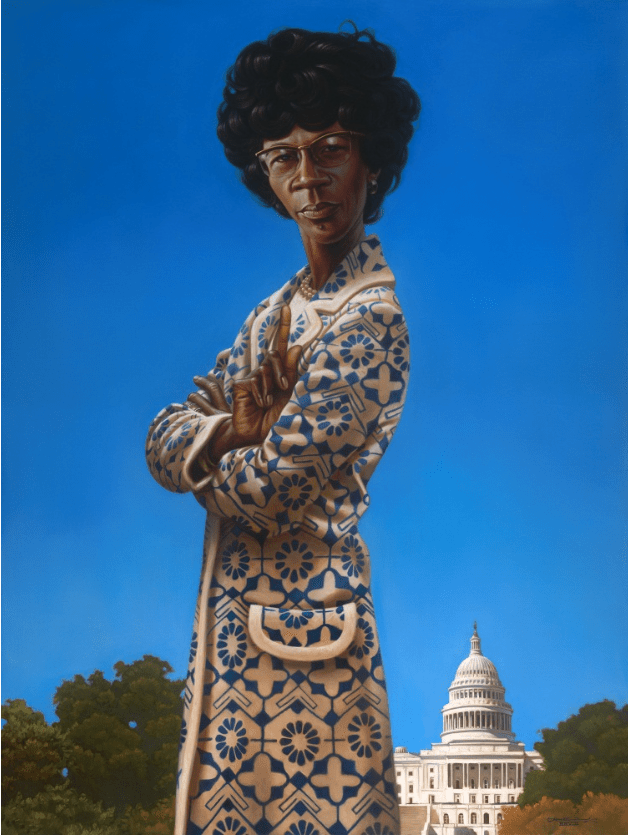

Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm achieved several firsts during her political career. She was the first African-American woman to win a seat in the New York State Assembly from Brooklyn. She was the first African-American woman to win a seat in the United States House of Representatives; in 1972, she became the first African American to campaign seriously for the presidential nomination of a major political party.

Chisholm had a reputation as a fearless, ambitious, and outspoken maverick. She studied the issues thoroughly and demonstrated utter confidence in her leadership ability. At the time, these qualities were typically only admired in men and would often cost her dearly for daring to display them as a woman. She was perhaps the quintessential feminist, a serious student of politics who saw no reason why she should hesitate to use her talents to serve others. Her bold leadership style was greatly appreciated by supporters and just as ardently disapproved by her opponents.

Growing Up in Barbados and Brooklyn

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born on November 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York, the oldest of four daughters of Charles St. Hill and Ruby (Seale) St. Hill. Her father was an emigrant from British Guiana (now Guyana) who worked as an unskilled laborer in a burlap factory in New York. Her mother, an emigrant from Barbados, was employed as a seamstress and a domestic. Because the family was poor, Shirley’s mother took her three-year-old daughter to live with her mother on the family farm in Barbados.

Shirley was later joined by two younger sisters who were also sent to live with their grandmother. Shirley and her sisters did not return to Brooklyn until she was eleven. During those formative years, she acquired the soft West Indian accent that would remain with her for life. She benefitted from the British elementary school system and the stern discipline preached by her loving grandmother, who instilled in young Shirley the virtues of pride, courage, and faith. She also learned to read and write before she was four years old. Shirley returned to New York in 1934 to find life very different than it had been in Barbados. Shirley’s hard-working parents moved to an apartment in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, where many more African-Americans lived. She experienced discrimination for the first time when she attended a school in racial transition.

Shirley did exceptionally well in school. In 1942, she graduated from Girl’s High School, a public school in Brooklyn, with an academic diploma and a medal in French. Although she was offered scholarships to Vassar and Oberlin, she turned them down because they were still too expensive for her parents. Instead, she chose to attend Brooklyn College, a subway ride away. She graduated cum laude with a degree in Sociology in 1946.

Her deep concern for children’s health and social development led her to pursue a career in child care. She earned a master’s degree in childhood education from Columbia University in 1952, a teacher certification, and a professional diploma in supervision and administration in education in 1961.

As a young woman, Shirley St. Hill taught nursery school at Mt. Calvary Child Care Center in New York from 1946 to 1952. She was a school director at the Friend In Need Nursery in Brooklyn from 1952 to 1953 and director of Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center in New York, where she was responsible for the administration and supervision of 24 teachers and maintenance of personnel catering to the physical, and emotional and intellectual needs of 130 youngsters between the ages of three and ten. She was also an educational consultant for New York’s Division of Day Care from 1959 to 1964.

Entering Democratic Politics in Bedford-Stuyvesant

On October 8, 1949, Shirley St. Hill married Conrad Chisholm, who she met at Columbia University. He worked for a private security agency that specialized in insurance claims for disability cases, a job that involved a great deal of travel. The Chisholm’s remained in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where Shirley became exceedingly active in local politics through the Democratic political clubs.

Because the regular Democratic organization did not welcome the ideas of an African-American woman, Chisholm helped form an independent political club called the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League (BSPL) and ran a door-to-door canvass and vote-getting campaign. The BSPL effort succeeded in electing the first black judge in Brooklyn history in 1953. In 1954 the BSPL proposed a full slate of black candidates. Although the slate was defeated by the regular organization’s candidates, Democratic leaders recognized the potential power of the new organization. Hoping to win over Chisholm and her followers, the regular party leaders elected her to the party’s local board of directors. The old trick of silencing critics by taking them in didn’t work; Chisholm continued to criticize the party’s policies and to put forth the case for adequate services to the people of her district. When the party leaders finally tired of her behavior and voted Chisholm off the board, she continued challenging them from the audience with the others who joined her. Chisholm would not stop until she achieved the goal of black representation at every level of government.

In the New York State Assembly

By 1964, Chisholm saw a chance to run for a seat in the New York State Assembly. She knew she would be stepping on a few toes of her male colleagues who were not ready to see a woman in a leadership position. After a very hard-fought campaign, Chisholm won the election to the New York Assembly. Her triumph was not without tragedy; however because her father died suddenly on the eve of her victory.

Chisholm developed a reputation for being a hard-working, studious, and disciplined legislator. Her support of the legislation was based on a detailed study from which she seldom wavered. As a member of the Assembly’s Education Committee, she continued her fight for underprivileged children and their families. Out of the 50 pieces of legislation, she introduced, eight passed, including the 1965 landmark SEEK Program (Search for Elevation, Education and Knowledge) which was designed to help African-American and Puerto Rican high school dropouts who had college potential to get into state universities while receiving remedial assistance. The controversial program opened educational opportunities to minorities and compensated for years of inadequate schooling in poor neighborhoods.

Her legislative agenda included helping domestic workers with unemployment insurance, protecting the tenure of female teachers after maternity leave, raising the maximum amounts of money that local school districts could spend on students, and providing state aid to daycare centers. She voted against public funds for private schools on constitutional grounds.

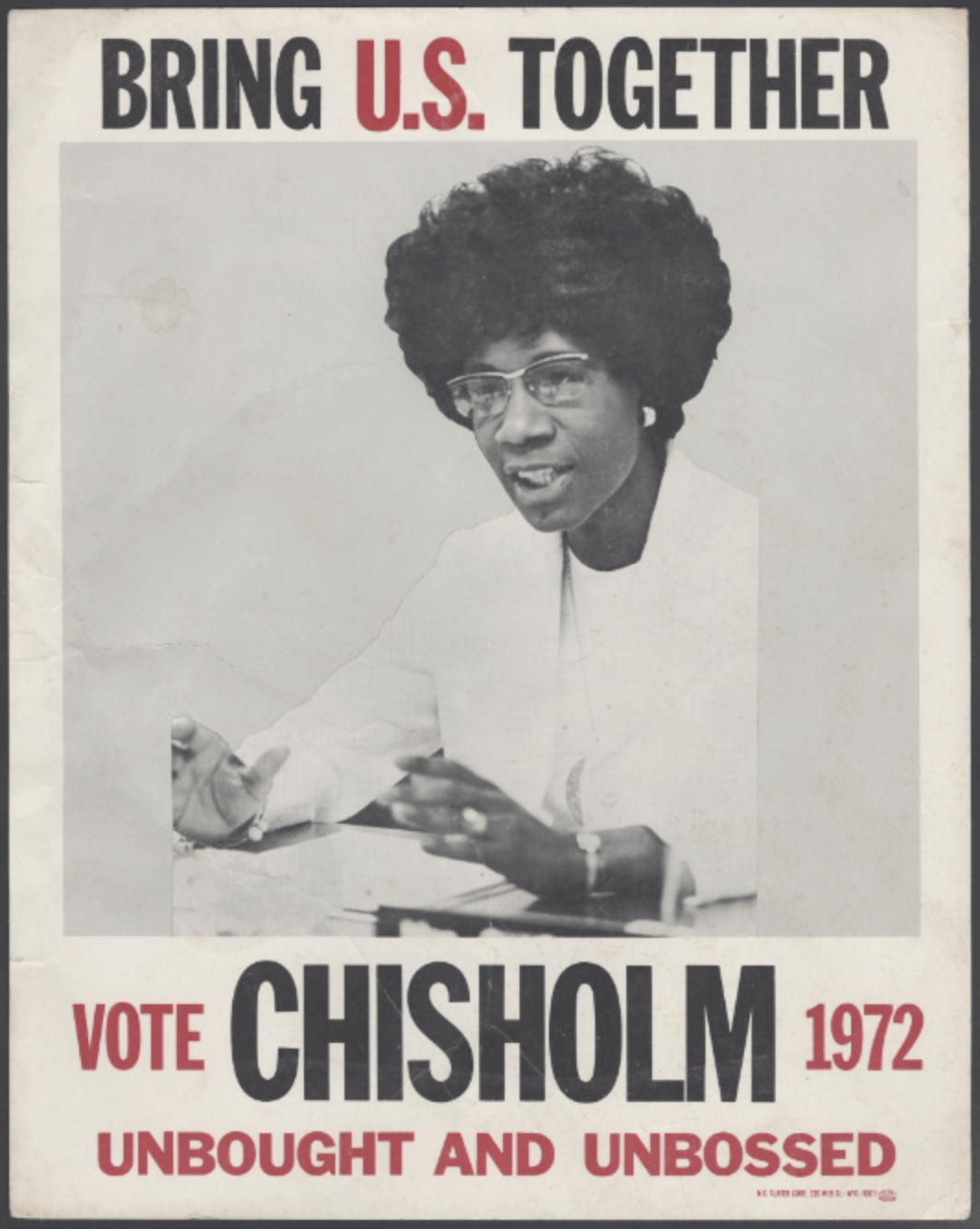

“Unbought and Unbossed”: Running for the U.S. Congress

Chisholm’s constituents appreciated her performance in the state legislature and rewarded her with reelection. By 1967, she focused on running for Congress due to a Supreme Court decision to create a new Congressional district in central Brooklyn. Chisholm was the first candidate to announce for the June 1968 primary, even though she knew the county Democratic organization would oppose her because she had been considered too independent and not a team player.

In the tough Democratic primary, she ran under the slogan “Unbought and Unbossed” and defeated two opponents, Dolly Robinson, a former labor leader, and the much favored State Senator William C. Thompson. Normally, a primary victory in that district would have been tantamount to winning the general election; but she found herself facing James Farmer, a nationally recognized civil rights leader, and former chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Moreover, he was the candidate of both the Republican Party and the Liberal Party, an important third force in New York politics.

Farmer’s well-funded campaign gained national media attention. Although both candidates stood for similar district concerns regarding employment, housing, education, decentralized local control of schools, and opposition to the Vietnam War, in the end Farmer could not overcome Chisholm’s advantage of running on the Democratic ticket in a heavily Democratic district.

Moreover, Chisholm proved to be a master campaigner playing on the fact that Farmer was an outsider whereas she had lived in the district and served its people most of her life. She was also helped by Farmer’s condescending attitude. His reference to her as “the little schoolteacher” who would not be taken seriously in Congress angered many women voters who happened to outnumber males by a large percentage in the district. Chisholm specifically appealed to women voters on issues of concern to them. She also reached out to the new Hispanic population with her ability to speak to them in Spanish. In the election of November 5, 1968, she defeated Farmer by a margin of two-and-a-half to one. In her victory celebration, Chisholm promised her supporters that she would not be quiet in Congress.

“That Disruptive Woman”: Chisholm’s Congressional Career

On January 3, 1969, Shirley Chisholm made history as the first African-American woman elected to the Congress of the United States when she was sworn into the 91st Congress and took her seat in the House of Representatives. When the Democratic members of the House Ways and Means Committee assigned her to the Agriculture Committee and its subcommittees on rural development and forestry, she protested loudly to the Party Caucus that these panels had no relevance for her Brooklyn constituency. She was widely quoted as having described those who made her assignment as gentlemen whose only knowledge about Brooklyn was that a tree grew in it. Although it was a bold move for freshman Members to question the party leadership, they relented and reassigned Chisholm to the Veterans Affairs Committee, which had more relevance for her constituents.

In March 1970, she gained a seat on the Committee on Organization, Study, and Review, which recommended reforms the Democratic Caucus adopted in 1971. In the 92nd through 94th Congresses she served on the Committee on Education and Labor. She was a member of the influential Rules Committee from the 95th through the 97th Congress.

For seven terms (1969-1983), Chisholm championed the social causes that had formed the heart of her career. She co-sponsored a bill calling for a 90 percent federal reimbursement of state welfare programs. As a member of the House consumer affairs study group, she co-sponsored a measure to establish a national commission on consumer protection and product safety. Chisholm proposed funding increases to extend the hours of childcare facilities and services to include working mothers of low-income families. She was most proud of her bill passed into law in 1974 that extended minimum wage coverage to domestic workers for the first time. She also urged making Martin Luther King’s birthday a national holiday.

Throughout her Congressional career, Chisholm consistently opposed military expenditures and American overseas military involvements. She joined a bipartisan coalition of 15 Members in her first term to introduce legislation to end the draft and create an all-volunteer military. She supported the successful effort in 1971 to repeal Section II of the Internal Security Act of 1950 which required suspected subversives to be interned in emergency detention camps. She chaired the Congressional Black Caucus Task Force on Haitian Refugees, She also opposed apartheid (racial segregation) in South Africa and called for an end to British arms sales to that country.

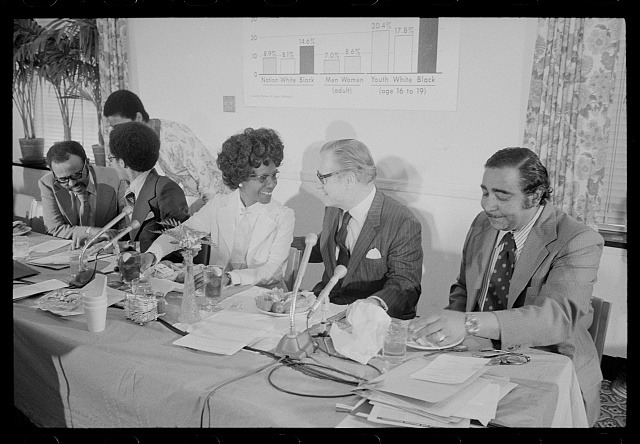

Representative Shirley Chisholm made history again by seriously campaigning for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 1972. Her candidacy caused a split in the Congressional Black Caucus, especially among some of her male colleagues, one of whom referred to her as “that disruptive woman.” At every step in her career, Chisholm had faced similar opposition from men who thought her ambitions unattainable because she was a woman. Moreover, her critics claimed Chisholm’s candidacy diverted attention from “more important issues.” She was serious about confronting the status quo and supported Geraldine Ferraro and Jesse Jackson in subsequent bids for the presidential nomination.

As a lawmaker, Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm was entirely devoted to serving her constituents. She was unafraid to assert herself on behalf of her principles and the well-being of the people of her district, especially the children. She believed politics should be a tool to effect change and secure a better way of life for all Americans. Fundamentally, Chisholm was a teacher committed to opening up the democratic process to people unaccustomed to thinking of themselves as having power. Her electoral battles were always hard-fought and hard-won, but with a celebration of the human spirit. Following her divorce from Conrad Chisholm in 1977, she married Arthur Hardwick, Jr., a New York state legislator. In 1982 Chisholm announced she would not seek reelection. Her decision was based on multiple considerations, the highest among them being her frustration with the rising tide of conservatism in Congress and the election of President Ronald Reagan. In addition, her husband, Arthur Hardwick, Jr., had been in a near-fatal automobile accident and passed in 1986 due to his failing health.

Celebrating “The Good Fight”

After leaving Congress, Chisholm continued fighting “the good fight” as a teacher, lecturer, writer, and activist. In 1983, she was appointed Purington Professor at Mt. Holyoke, a women’s college in Massachusetts, where she taught politics and women’s studies. She co-founded the National Political Congress of Black Women, which sent a delegation of over 100 women to the 1988 Democratic National Convention. She participated in the 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns of Jesse Jackson because she shared many of his goals for supporting disadvantaged communities. President Clinton nominated her to become Ambassador to Jamaica, but she declined for health reasons. She spent much of her retirement writing, lecturing, and teaching.

Chisholm received over 35 honorary doctoral degrees and won more than 14 awards from national and international organizations such as the National Press Club, the United States Department of State, and UNESCO. She was honored with the Woman of the Year Award from Clairol in 1973 for her outstanding achievement in public affairs.

—

This article is an adaptation from the U.S. Capitol Historical Society’s 1995 book “Outstanding Women Members of Congress” by Dr. Shirley Washington.