Recently, discussion of the American military conscription draft system permeated news outlets, since last week the Supreme Court declined to take the case NATIONAL COALITION FOR MEN, ET AL. v. SELECTIVE SERVICE SYSTEM, ET AL., which confronts the longstanding tradition of a male-only draft in the United States. In her statement regarding the case, Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Breyer and Kavanaugh, explained that the Court’s reasoning for not taking the case is due to the fact that Congress is already in the process of revising the draft system. The statement does note, however, that women’s role in the military has increased dramatically since the gendered system of the draft was last upheld in a 1981 ruling, and that every role in the military has been available to women since 2015.

Congress is currently sponsoring the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service to reevaluate multiple aspects of the military, including the draft. In its final report, released on March 25, 2020, the Commission recommended “revisions intended to update existing legislation to promote equitable obligations in the event a draft is enacted,” with one of the primary objectives to “eliminate male-only registration and expand draft eligibility to all individuals of the applicable age cohort.” The Commission sought to justify this recommendation by explaining that “[m]ale-only registration sends a message to women not only that they are not vital to the defense of the country but also that they are not expected to participate in defending it.” Due to the presence of this commission, the Supreme Court believes it should not take this case due to its tradition of deferring to Congress in matters of Defense.

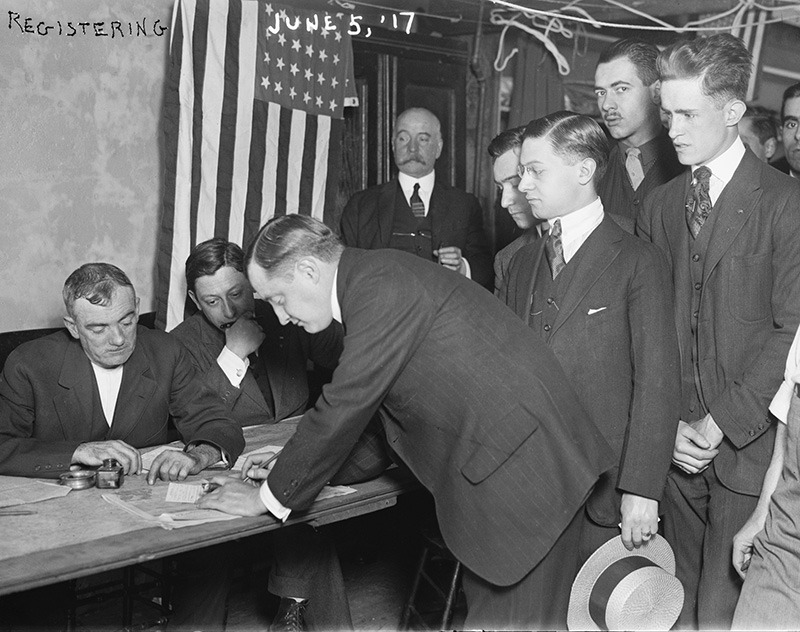

The draft has a long and significant history within American government. Started during the American Revolution when militia drafts were utilized to maintain the Continental Army, conscription has operated through six major wars, including the Civil War, World War I, World War II, Korean War, and Vietnam War. In its beginnings, conscription included relatively relaxed requirements that went somewhat unenforced; over time, however, rules surrounding the draft became more standardized. Early forms of the draft before and during the Civil War provided broad options for substitution, commutation, and exemptions. Local areas had individualized and constantly evolving requirements, and many did not have the bandwidth to enforce them completely. The Enrollment Act of 1863 made military conscription consistent across the country by transitioning control of the draft to the federal government.

When Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act (1940), it established for the first time a peacetime draft, to help manage global tensions resulting from the preceding world war. When President Carter introduced the Presidential Proclamation 4771 in 1980, it created the current system in which eligible individuals must still register for the draft even if conscription is not in effect. Currently, while citizens have not been inducted into service since 1973, men are still required to register within thirty days of their eighteenth birthday in case it is ever needed. The Selective Service System currently facilitates this registration through many platforms, including an area on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), online registration by Social Security number, and by mail through entities such as the Departments of Motor Vehicles, Education, and Homeland Security.

When a national emergency occurs and a draft is enacted, Congress must amend its previous conscription legislation, the Military Selective Service Act, to enable the President to initiate the draft process. The lottery for the draft is televised and streamed, and individuals are ordered to report based on the order of birth dates chosen.

American attitudes towards the draft have varied over time but remain largely negative. Public opposition to compulsory military conscription presented itself as early as the beginning of the nineteenth century. One of its loudest critics, Daniel Webster, gave a speech to Congress on December 9, 1814, in which he urged them to forgo a draft in preparation for the War of 1812. He argued that conscription necessitated the loss of “the most essential rights of personal liberty” and that there is nothing more “absurd” than giving the government “an uncontrolled power of military conscription.” During periods of anti-war sentiment, such as the Vietnam War-era, criticism of military conscription is harshest. However, there have been a few moments in time, such as the late 1970s, when there was a movement among civilians to revive and strengthen the draft. In 1979, for instance, a movement to “revitalize” the draft became popular in order to increase military preparedness and the efficiency by which the draft is assembled. According to a recent study, seventy-four percent of Americans are currently not in favor of reinstating a compulsory draft. In terms of equity based on racial and economic status, the draft also has a problematic history; coined the “poverty draft” by some individuals, conscription historically results in individuals of color and low economic status being drafted at much higher rates than their wealthier white counterparts. In the military conscription for World War I, for example, Black Americans were drafted at a rate of 34.10% while only 24.04% of white Americans were drafted. Despite the absence of any specific discrimination within the legislation of the draft, provisions exempting groups such as college students and occupational deferments inherently protect certain groups while excluding others. This outcome is especially evident in the draft for World War II, in which Americans of color were given deferments at disproportionately low rates for every category except agricultural deferment.

Ultimately, it appears that Congress will have the final say in any changes that surround qualifications for the draft. If a change in gender requirements or other historic modification in the exemption rules occurs, it will simply be the next step in a conscription system which has evolved to fit the needs of the United States military since the eighteenth century.

Written by guest contributor Maeve Silk, a student at Georgetown University studying history and English and minoring in art history. Edited by U.S. Capitol Historical Society staff.

Sources:

https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/

https://www.supremecourt.gov/orders/courtorders/060721zor_6537.pdf

https://inspire2serve.gov/reports/final-report

https://www.sss.gov/about/return-to-draft/#s1

https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/10/05/chapter-5-the-public-and-the-military/