The placement and eventual removal of two statues in front of the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C. is an oft-forgotten piece of American history, pertinent to our observance of Native American Heritage Month. The Rescue and The Discovery of America both included harmful stereotypes of indigenous people next to white figures in positions of power. For nearly a century, members of Congress walked past these statues to enter the Capitol. But due to the criticism of advocacy organizations like the National Congress of American Indians and individual activists like Leta Myers Smart, these statues were both taken down—a powerful example of indigenous activism in the mid-20th century.

In 1836, future president James Buchanan (then a Senator from Pennsylvania) headed a movement to commission two statues to flank the entrance to the Capitol building. Selected was Luigi Persico, an Italian-born sculptor who already created several statues for the exterior of the Capitol. Some members of Congress expressed dissent at the prospect of a non-American artist creating such important work; thus American-born Horatio Greenough was selected to sculpt the companion piece. In the following months, a proposal worked its way through Congress and to then President Martin Van Buren, who authorized Persico and Greenough to create the statues.

Persico’s Discovery of America was finished and installed in front of the Capitol by 1844. It depicted a triumphant Christopher Columbus holding up a globe next to a cowering American Indian woman. Symbolically, Columbus was shown confidently taking a step forward, while the Indian woman appeared intimidated and rooted in place, in a defensive stance.

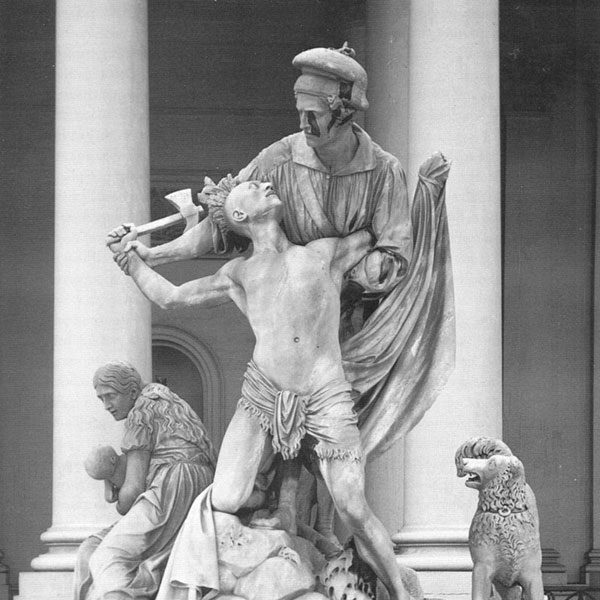

On the other side of the staircase, Greenough’s The Rescue featured a more explicitly violent altercation between indigenous people and white settlers. The centerpiece of the statue depicted a calm, strong frontiersman towering over an American Indian warrior with a tomahawk. Behind them, a frightened woman clasped a small child, and nearby, a dog looked on in horror. The implication is that the Indian threatened the lives of this small pioneer family, and the patriarch stepped up to protect them. The emotion on the Indian’s face revealed fear, while the frontiersman is in complete control. Greenough himself wrote that the statue was meant “to convey the idea of triumph of the whites over the savage tribes.”

The central theme of these sculptures ultimately promoted the idea of Manifest Destiny; that Americans were destined to take control and civilize the lands that became the United States. These false and offensive depictions of white men as more powerful and capable than indigenous people reflected and reinforced the belief that violence in the name of westward expansion was justified. At least one member of Congress was conscious of the connection between these statues and their promotion of manifest destiny. James Belser, a representative from Alabama, said, “Let gentlemen look on the two figures which have so recently been erected on the eastern portico of the Capitol and learn an instructive lesson…The artist, when he made Columbus the superior of the Indian princess in every respect, knew what he was doing.” Whether consciously or subconsciously, this idea no doubt permeated through some members of Congress as they discussed the annexation of Texas, Oregon, and California in order to spread American influence across the West.

For their part, American Indian groups always opposed the creation and installation of these statues. Their dissent became even more vocal in the 1950s under the leadership of Smart, a member of the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska. She became active in Native political organizations (such as the National Congress of American Indians) after her negative experiences with the Office of Indian Affairs, which participated in the forceful assimilation of Native children in boarding schools. During this period, she began a campaign that called for the removal of The Rescue and The Discovery of America by writing open letters to magazines and organizations like the National Sculpture Society. Her criticisms drew attention to the physical and sexual violence depicted in the statues, as well as the cultural violence they promoted. She knew that only a legislative act could remove the sculptures and, therefore, submitted petitions to Congress that stated that the statues were “misleading to the general public in that they fail to portray the true character of the American Indian.”

Several indigenous activist groups and individual members of Congress supported Smart’s petitions. Many thought, however, it was impossible to persuade Congress to pass legislation to remove the sculptures. But in 1958, the Capitol building underwent an extensive renovation project, which provided the necessary vehicle to achieve that end.

The decision on whether to retain the statues was taken away from the larger Congress and given to the five-man ‘Commission for the Extension of the United States Capitol,’ made up of the Vice President, the Speaker of the House, the minority leaders of both chambers, and the Architect of the Capitol. This small group made the determination that year to remove the statues in accommodation with the extension of the building. The campaign to remove the statues was the most important factor. But the statues had also deteriorated significantly after being exposed to the elements during their century-long display along the steps of the Capitol. Restoration would be very expensive. So, while the dog from The Discovery of America is on display in the Middlebury College Museum of Art, the rest of the statues remain in storage.

The success of Smart and her allies speaks to the determination of American Indians to ensure a place of dignity for themselves in our nation’s capital. Indigenous people always lived in the land that is now Washington, D.C. The cultural narrative authored by colonialism attempted to rewrite their role into weak, submissive, incapable bystanders, as depicted in the two statues discussed. The removal of these statues was a meaningful step that put indigenous stories back under the control of indigenous people.

Written by guest contributor Kate Ashman, a senior at Brigham Young University majoring in American Studies. Edited by U.S. Capitol Historical Society staff.

Sources:

Fryd, Vivien Green. Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough’s “Rescue” and Luigi Persico’s “Discovery of America”

Genetin-Pilawa, C. Joseph. A Curious Removal: Leta Myers Smart, The Rescue, and The Discovery of America. The Capitol Dome.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1956-10-12/ed-1/seq-40/